Supply Chain Chronicles: What If SCM Analysts Existed 400-600 Years Ago?

25-Aug-2025 - SCM4ALL Team

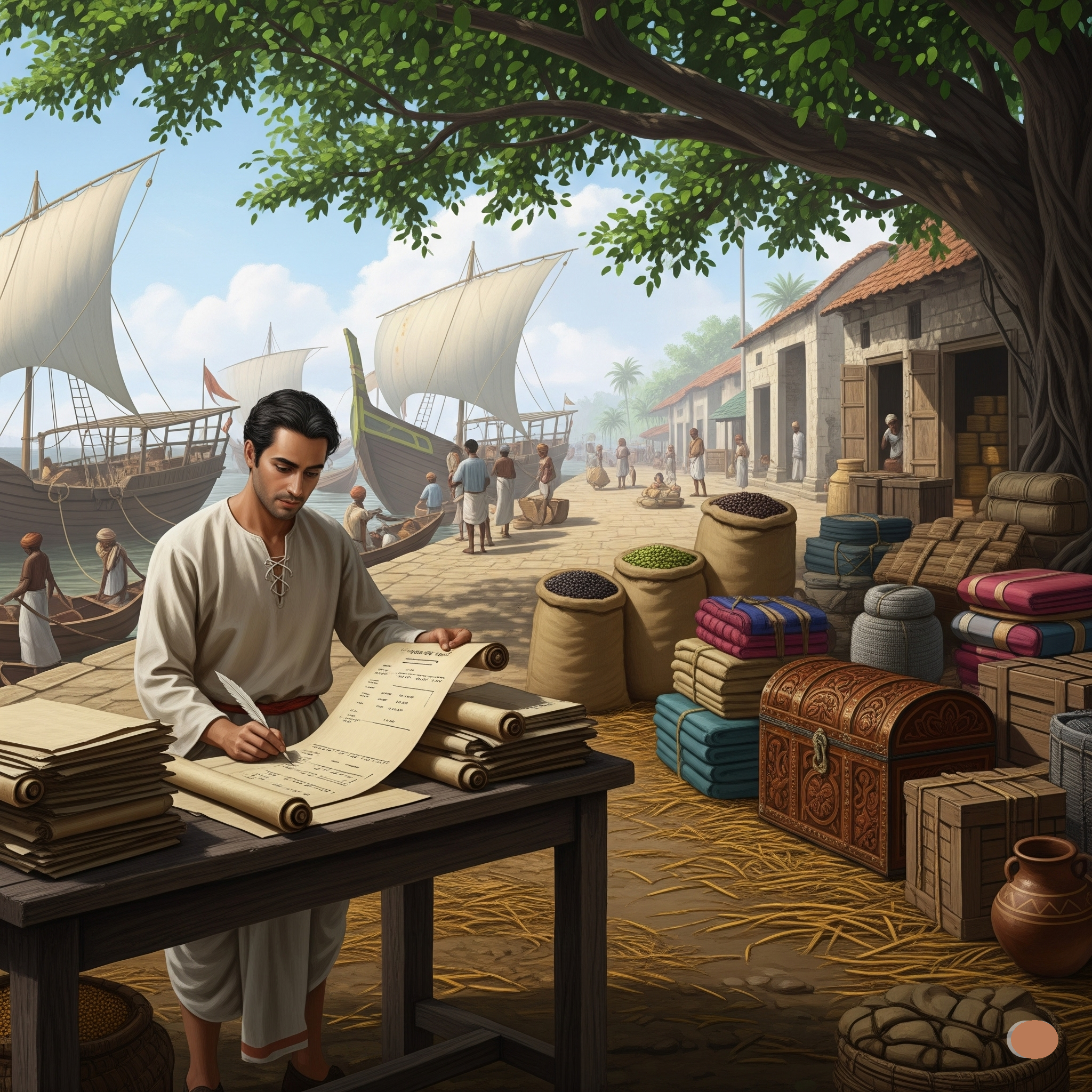

Picture this: it’s the 14th century, and global trade is booming. Spices sail from India to Arabia, silk flows from China to Europe, and merchants haggle in bustling ports from Calicut to Venice. Now, imagine four supply chain analysts stationed at the world’s top trading hubs—Calicut (India), Hormuz (Arabia), Venice (Western Europe), and Quanzhou (China) —scribbling notes in modern supply chain management (SCM) jargon. They’re wrestling with lead times, demand forecasting, and pirate-induced disruptions, all while navigating local politics and monsoon winds. This is a look at what they might have thought, if they were donning the hats of their modern counterparts!

Calicut, India: Raman Nair’s Spicy Struggles

In the steamy port of Calicut on India’s Malabar Coast, Raman Nair, a sharp-eyed analyst, oversees the spice trade. Calicut is the epicenter of pepper and cardamom exports, with merchant guilds (urukkal) and ship captains (nakhuda) driving the chaos of the docks. “Supply chain visibility is a nightmare,” Raman writes, as goods move from hinterland farms to port warehouses without a trace. He proposes a logbook (khanjari) to track inventory.

Inventory management is another headache. Raman notes that poor demand forecasting led to a cardamom surplus after Venetian galleys canceled orders. He also points out that local merchants are hoarding spices, which disrupts just-in-time delivery. He believes they need to optimize warehouse capacity and align with seasonal trade winds.

Last-mile delivery is no easier. Coastal boats struggle to ferry goods to anchored ships during monsoons, and Raman suggests that a dedicated fleet of smaller vessels could streamline transshipment. Risk management is also a concern, as pirates on the route to Hormuz are a "supply chain killer". Diversifying routes via Cochin and hiring armed escorts is a must.

Hormuz, Arabia: Omar ibn Khalid’s Desert Hub

In the sun-scorched port of Hormuz, Omar ibn Khalid manages the flow of spices, textiles, and horses through a critical transshipment hub. While the market overseer (muhtasib) keeps trade humming, Omar sees room for improvement.

He notes that their strategic location optimizes trade networks, but the trade emporium (qaisariyya) is a bottleneck. Customs delays for Indian cotton and Chinese silk inflate lead times, and a streamlined clearance process could cut days off delivery.

Supplier relationships are also tricky. Omani horse suppliers are unreliable due to tribal feuds, and Omar believes that building trust with Bedouin intermediaries could stabilize the supply for Indian buyers. Demand forecasting is another puzzle, as frankincense demand in China fluctuates wildly. He suggests that the market overseer needs caravan data to predict seasonal spikes. Logistics infrastructure also poses challenges, as sandstorms disrupt overland routes to Baghdad. He notes that investing in irrigation systems (falaj) for oasis waypoints could boost caravan reliability.

Venice, Western Europe: Lorenzo Contarini’s Maritime Ambitions

In Venice, the gateway to Europe, Lorenzo Contarini tracks the flow of spices, silk, and luxury goods via Mediterranean galleys. The doge (ruler) demands efficiency, but the merchant warehouses (fondaco) and trading galleys (galea) are a logistical maze. “Supply chain integration is abysmal,” Lorenzo grumbles, noting that merchants from Alexandria and Constantinople operate in silos, causing stockouts of Indian pepper. He believes a centralized platform could coordinate orders.

Fleet management is another pain point. The galley convoys to the Levant face Ottoman inspections, delaying transit. Optimizing sailing schedules and negotiating faster port clearances could save 20% on lead times. He also notes that high tariffs in Alexandria inflate silk procurement costs. He writes that direct sourcing from Hormuz could bypass intermediaries and boost margins.

Lorenzo also considers sustainability, noting that slave labor for galley rowing is unethical and risky. He suggests that wind-powered vessels could future-proof their maritime logistics.

Quanzhou, China: Zhang Wenxiu’s Bureaucratic Balancing Act

In Quanzhou, a bustling port on China’s Fujian coast, Zhang Wenxiu oversees porcelain, silk, and tea exports under the Ming dynasty’s maritime trade office (shibo si). He notes that end-to-end supply chain coordination is weak, and inland kilns are out of sync with exports. He suggests a "supply chain control tower" could align production with shipping schedules.

Reverse logistics is a growing issue. Defective Indian cotton bales clog warehouses, and a returns process is needed to handle rejects efficiently. Capacity planning is another challenge, as Admiral Zheng He’s fleet is overcapacity for Southeast Asia but underutilized for Arabia. Zhang Wenxiu believes reallocating vessels could optimize trade flows.

Compliance is the biggest hurdle. The sea ban (haijin) policies create regulatory bottlenecks, and lobbying the local official (tongzhi) for exemptions could expedite approvals.

Comparative Insights: Medieval SCM Woes

These analysts, worlds apart, share timeless supply chain woes: poor visibility, shaky demand forecasting, and external risks like pirates, monsoons, or imperial decrees. Yet each port has its flavor. Calicut battles monsoon logistics and guild rivalries. Hormuz juggles overland and maritime flows. Venice obsesses over costs and maritime supremacy. Quanzhou wrestles with bureaucratic red tape.

Pirate attacks mirror modern cybersecurity or geopolitical threats. Venetian tariffs echo today's trade wars, and Quanzhou’s regulations resemble modern compliance hurdles. Medieval or modern, supply chains are a delicate dance of coordination and resilience.

This is a fun take only ! Only approximately based on older trading challenges, they are all just are approximations ":)"