The Anatomy of a Warehouse: Understanding Zoning, Flow, and Efficiency.

10-Jan-2026 - SCM4ALL Team

Explore how the physical design of a warehouse dictates the speed, cost, and reliability of the entire supply chain. From traditional zoning strategies to the rise of autonomous robotics, learn why the right layout is a logistics professional's ultimate competitive advantage.

Most people outside the industry see a warehouse as little more than a giant box where stuff sits until it’s needed—a static holding pen. But for a Supply Chain Management (SCM) professional, a warehouse is a high-speed, high-frequency engine. It is a dynamic organism that breathes in inventory and breathes out customer orders.

The efficiency of this engine doesn't just happen. It is engineered. If the "pipes" (aisles) are too narrow, the flow chokes. If the "fuel" (fast-moving inventory) is stored too far from the engine, energy is wasted. In the low-margin world of logistics, these physical inefficiencies translate directly into lost profits and unhappy customers.

For beginners in SCM, understanding the physical manifestation of a warehouse—its layout and zoning—is foundational knowledge. This guide will walk you through the physical artifacts, the strategies of flow, the high stakes of design, and how technology is fundamentally reshaping the very walls of the modern warehouse.

1. The Physical Artifacts: The "Hardware" of the Warehouse

Before we can design a layout, we must understand the building blocks. A warehouse isn't just empty space; it is a collection of physical artifacts designed to manage the realities of gravity, volume, and movement.

The Docks (The Mouths)

Docks are the critical points of entry and exit. They are where the warehouse interfaces with the outside transportation network (trucks/trailers). Their placement on the building's perimeter dictates the entire macro-flow of operations.

Racking Systems (The Skeleton)

Real estate is expensive; air is free. Racking systems exist to utilize vertical space. The type of rack you choose defines your storage density and accessibility. A "Selective Rack" allows you to pick any pallet at any time but uses a lot of aisle space. A "Drive-In Rack" allows for ultra-high density but buries inventory behind other pallets, making it suitable only for bulk storage of the same SKU.

Aisles (The Arteries)

Aisles are necessary evils. They are empty spaces required for navigation by humans and equipment (like forklifts). The width of an aisle is a constant trade-off. Wide aisles are safer and faster to navigate but waste precious floor space. Narrow aisles maximize storage but require specialized, expensive materials handling equipment (MHE) and slow down movement.

Staging Areas (The Buffer Zones)

Goods rarely move instantly from a truck to a rack. Staging areas are open floor spaces near docks used for buffering. Inbound staging allows for quality checks and sorting before "put-away." Outbound staging allows orders to be consolidated and wrapped before being loaded onto a truck.

2. The Logic of Flow: Macro-Layout Strategies

How do you arrange these artifacts? The primary goal of warehouse design is to create a smooth, unidirectional flow of goods that minimizes touches and travel distance. There are two primary macro-layouts used today: U-Flow and I-Flow.

Choosing between these depends largely on your building's physical shape, your volume of goods, and your security needs.

Comparison: U-Flow vs. I-Flow Layouts

| Feature | U-Flow Layout (The Most Common) | I-Flow Layout (Straight-Through) |

|---|---|---|

| Configuration | Shipping and Receiving docks are located on the same side of the building. Goods enter, loop around storage, and exit near where they entered. | Shipping and Receiving docks are on opposite sides of the building. Goods flow in a straight line from one end to the other. |

| Primary Benefit | Resource Sharing: Staff and equipment (like forklifts) can easily shift between receiving and shipping duties depending on workload peaks. | No Backtracking: Excellent for high-volume operations where goods need to move fast without "looping" or crossing paths with inbound traffic. |

| Cross-Docking Potential | High. Goods can be moved immediately from an inbound dock to an adjacent outbound dock with minimal travel. | Excellent. Goods flow directly across the floor from receiving to shipping terminals. |

| Security | Higher Security: Only one side of the building, or one main yard gate, needs to be monitored for external entry and exit. | Moderate Security: Requires monitoring and staffing at two separate ends of the facility. |

| Best Applicability | Small to medium warehouses; businesses with seasonal peaks requiring flexible labor. | Very large distribution centers; high-velocity "Fast-Moving Consumer Goods" (FMCG) sectors. |

3. The Science of Zoning: The "Heat Map"

Once the macro-layout is decided, you must determine where specific products live. This is called zoning. You cannot simply place items alphabetically; that spells disaster for efficiency.

Zoning is usually based on the nature of the goods (e.g., hazardous materials need their own fire-rated zone) or, most commonly, the velocity of the goods (how fast they sell).

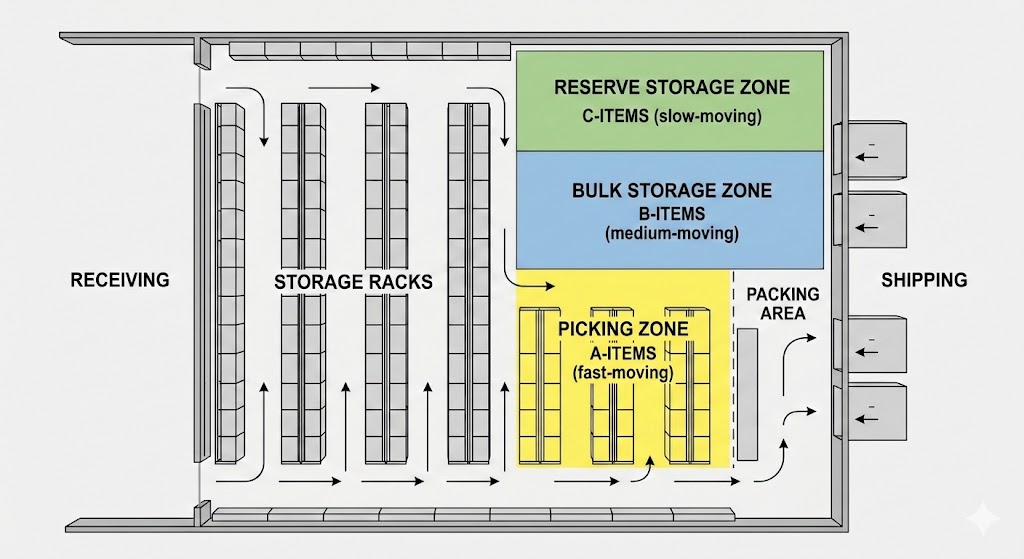

ABC Zoning (Velocity-Based)

This is the gold standard for most retail and e-commerce warehouses. It is based on the Pareto Principle (the 80/20 rule), which states that roughly 20% of your items will account for 80% of your picking activity. We visualize the warehouse as a "Heat Map."

- Zone A (The Hot Zone): Your top 20% fastest-moving SKUs. These are placed in the "golden zone" (chest height racks to avoid bending or reaching) and are located closest to the shipping docks or packing stations to minimize travel time.

- Zone B (The Medium Zone): Items that sell regularly but not daily. These occupy the middle aisles or higher/lower rack levels.

- Zone C (The Cold Zone): Slow movers, seasonal items, or bulk overstock. These are placed in the deepest corners of the warehouse, furthest from shipping, or on the very highest racks that take longer to access.

Industry-Specific Zoning Examples

While ABC is common, different industries have unique physical requirements tailored to their supply chain needs:

- Pharmaceuticals & Food (Condition-Based Zoning): The layout is dictated by temperature. You will have distinct, insulated zones for Frozen (-20°C), Chilled (2-8°C), and Ambient temperature goods. There are also strict regulatory zones for controlled substances that require cages and biometric access.

- Automotive & Heavy Manufacturing (Size-Based Zoning): The layout is defined by the physics of the parts. Bulk zones near docks handle heavy items like engines or chassis that require overhead cranes. Separate zones with high-density shelving handle thousands of small parts like screws, sensors, and washers.

- E-commerce (Velocity & Volatility): E-commerce demands extreme flexibility. Zoning might change seasonally or even weekly based on promotions. "Hot" items are often moved to forward-pick zones right next to the packing conveyor belts.

4. The Stakes: How Layout Affects SCM Performance

A warehouse layout is the "circuitry" of your supply chain. If the wiring is faulty, the entire system shorts out. The impact of layout on broader Supply Chain Management performance is profound.

The Cost of a Bad Layout: The "Hidden Tax"

A poorly designed layout acts as a tax on every single order you process. Over time, this bleeds profitability.

- The Travel Time Trap: In a non-optimized warehouse, pickers can spend 60% to 70% of their day just walking or driving an empty forklift. They are being paid to travel, not to pick. If a bad layout adds just 60 seconds of travel time per order, and you ship 2,000 orders a day, that is over 33 hours of wasted labor every single day.

- Ghost Inventory and Inaccuracy: Cramped, disorganized zones lead to items being misplaced. The system says the item is in stock, but the picker can't find it. This leads to "ghost inventory," stock-outs, and unnecessary re-ordering, inflating carrying costs.

- Safety and Bottlenecks: Poorly planned traffic flows lead to congestion at intersections. This not only slows down throughput but significantly increases the risk of collisions between forklifts and pedestrians.

The SCM Advantage of a Good Layout

Conversely, a strategic layout is a competitive advantage.

- Throughput Velocity: An optimized flow reduces "dock-to-stock" time (how fast received goods are available for sale) and "order cycle time" (how fast an order gets out the door).

- Scalability: A modular, well-zoned layout can absorb spikes in demand (like Black Friday) without collapsing into chaos.

- Enabled Cross-Docking: A good layout facilitates cross-docking—the practice of moving inbound goods directly to outbound trailers without ever putting them into storage. This is the holy grail of SCM efficiency as it eliminates storage costs entirely for those items.

5. The Future: Technology and Physical Manifestation

We are currently living through a revolution in warehousing. Until recently, warehouses were designed around the limitations of humans and forklifts. Technology is now removing those limitations, fundamentally changing the physical manifestation of the building.

Shrinking the Aisles: VNA and ASRS

Traditional aisles had to be 10–12 feet wide to allow a forklift to turn around. That's a lot of wasted "air."

Modern Very Narrow Aisle (VNA) trucks are wire-guided and don't need to turn, shrinking aisles to under 6 feet. Taking it further, Automated Storage and Retrieval Systems (ASRS) use robotic cranes on tracks. They require almost zero aisle space, turning the warehouse into a solid block of high-density inventory, utilizing every cubic inch of vertical space.

The "Fluid" Warehouse: AMRs

In the past, racks were bolted to the floor. Zoning was semi-permanent. Today, Autonomous Mobile Robots (AMRs) are changing that. Some AMR systems, like "goods-to-person" robots, physically lift entire shelving units and bring them to a stationary human picker.

This means the physical layout is no longer static; it is fluid. The robots can automatically re-zone the warehouse overnight based on tomorrow's predicted order profile, moving "hot" racks closer to the pick stations while the warehouse sleeps.

The Rise of the "Dark Warehouse"

As automation takes over certain zones, the need for human-centric design disappears. We are seeing the rise of "lights-out" or "dark" warehouse zones. These areas require no lighting, no heating or cooling, and no wide pathways for humans to walk safely. They are dense, efficient, machine-only environments designed purely for mathematical optimization of space and speed.

Conclusion

For us, the students and learners of SCM, the key takeaway is this: A warehouse layout is never "finished." It is a continuous process of analysis and adaptation. As markets shift, product mixes change, and technology advances, the physical space must evolve. Mastering the geometry of the warehouse is mastering the speed and reliability of the entire supply chain.